Protected areas play a key role in the conservation of biodiversity. While many should see the light of day by 2030 following the Kunming-Montreal agreement , it is essential to think about their location in order to best anticipate future threats to biodiversity.

Thus, in the Mediterranean, many wetlands threatened by major future changes in climate and land use are still not protected. This situation could compromise the adaptation to climate change of the birds they shelter.

The key role of protected areas

Protected areas , such as nature reserves, national parks or the network of Natura 2000 sites, are spaces that help conserve biodiversity.

Indeed, they locally limit certain pressures of human origin which weigh on the species and their habitats, such as the artificialization of the soil, the intensification of agricultural and forestry uses, or even hunting. The application of these protective measures also facilitates the adaptation of species to climate change.

In order to bend the curve of biodiversity loss, member states of the Convention on Biological Diversity adopted the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework in late 2022. The latter includes an ambitious objective to protect 30% of land and sea surface by 2030 (“30x30 Objective”) which should strongly encourage countries to create new protected areas. One of the current challenges is therefore to identify the areas to be protected as a priority in a world subject to profound current and future changes.

Logically, protection measures should be applied as a priority to areas that are home to biodiversity that is both rich, original and particularly threatened. However, in the past, protected areas have often been created in areas that are not easily accessible , so as to minimize conflicts with human activities .

In addition, the choice of areas to be protected has most often not taken into account the pressures that could be exerted on species and their habitats in the coming decades, even though the creation of protected areas can make it possible to anticipate their effects. This is particularly the case for the destruction of natural habitats linked to urbanization or the extension of agricultural land.

The case of birds in Mediterranean wetlands

The Mediterranean basin is a “biodiversity hotspot ” . Indeed, by its geographical position at the crossroads of three continents, it is home to an exceptional biodiversity. Historical cradle of many civilizations, biodiversity is also extremely threatened by human activities .

In this region, Mediterranean wetlands occupy a special place. Essential for the conservation of a large number of species, including many migratory birds, they are also strongly subject to the development of human activities in a context of water resources under pressure. However, Mediterranean wetlands are still too little protected .

In a study coordinated by the Research Institute for the Conservation of Mediterranean Wetlands of the Tour du Valat and the Center for Ecology and Conservation Sciences of the National Museum of Natural History, we sought to identify the areas wetlands of the Mediterranean basin to be protected as a priority in the face of future global changes in order to facilitate the adaptation of birds to climate change.

Indeed, in response to the increase in temperature, species tend to move towards the poles and in altitude in order to follow the shift in their preferential thermal conditions. However, if this process is limited by the destruction of natural habitats , it is on the other hand facilitated by the establishment of protected areas .

[ More than 85,000 readers trust The Conversation newsletters to better understand the world's major issues . Subscribe today ]

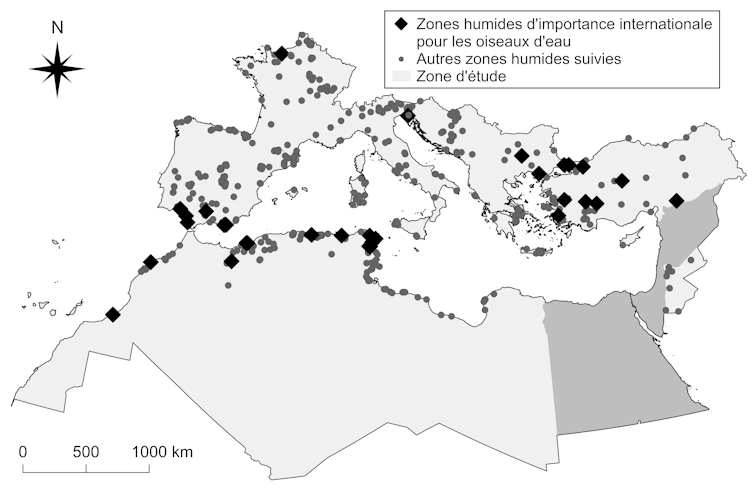

First, we mobilized data from nearly 3,000 wetlands in 21 Mediterranean countries, monitored as part of the International Waterbird Census , one of the oldest citizen science protocols.

In the Mediterranean, it makes it possible to monitor the state of the populations of more than 150 species of birds that are highly dependent on wetlands, such as ducks, gulls or the emblematic pink flamingo. These data made it possible to assess the birds' tolerance to temperature changes.

We then calculated for all the wetlands studied the increase in temperature and the conversion of natural habitats expected in the future. For this, we based ourselves on the most recent climate and land use scenarios for the end of the 21st century from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Combined with the species' tolerance to temperature changes, this information made it possible to calculate for each wetland an index of future “difficulties” in adapting bird communities to global warming.

A current network of relevant but insufficient protected areas

We have thus shown that in the Mediterranean, the current protected areas, and in particular those benefiting from the most restrictive regulatory measures, are rather well located.

Indeed, they generally cover wetlands, whose bird communities, in the absence of protective measures, could have experienced significant adaptation difficulties in the coming decades, due to the rise in temperatures. and significant destruction of natural habitats.

The protection measures already in place in these wetlands should therefore facilitate the adaptation of birds to climate change.

However, we have identified nearly 500 wetlands whose bird communities could face significant adaptation difficulties, and which are currently not subject to any protection measures.

Among them, 32 are qualified as “internationally important” for waterbirds , ie they present a major issue for the conservation of birds according to the criteria of the Ramsar Convention on wetlands .

Among the wetlands to be protected as a priority, and in particular those with a major stake in the conservation of birds, many are located in the countries of the Maghreb and the Near East.

This result thus underlines the urgency of creating new protected areas in these countries, whose "Key Biodiversity Areas" (sites with a major stake in the conservation of biodiversity in general) are still too little protected even though they are strongly threatened by future changes in climate and land use.

The importance of taking into account the destruction of natural habitats

This study also underlines the essential role played by the destruction of natural habitats which, despite less media coverage than climate change, should remain a major threat to biodiversity in the coming decades.

Taking it into account, in the same way as the effects of climate change on biodiversity, is therefore crucial in the planning of conservation measures such as the creation of protected areas, but also more broadly in all of our interactions with living organisms. if we want to give ourselves the means to halt the decline of biodiversity.

Fabien Verniest , Post-doctoral researcher in conservation biology, National Museum of Natural History (MNHN) and Isabelle Le Viol , Ecologist, conservation biologist, teacher-researcher at the MNHN, National Museum of Natural History (MNHN)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .