How can young generations, current and future, show empathy and want to preserve a natural world threatened by human activities, when this world is disappearing faster and faster and these adults of tomorrow know less and less about it? ?

In other words: how can we feel connected to other living beings or environments if we have never met them?

The IPBES reports document this decline in life and alert us: today, 75% of the surface of continental ecosystems and 40% of the oceans have been seriously degraded; a million species are threatened with extinction in the short term.

A dwindling experience of the non-human

In a highly acclaimed work published in 2005, Last Child in the Woods (translated into French under the title A Childhood in Freedom ), the American journalist Richard Louv drew up the observation of a youth increasingly distant from natural spaces and outdoor activities.

“Our society teaches young people to avoid direct experience with nature. »

A situation that does not spare France, as highlighted by work made public in 2015, showing that during school days, 39% of children aged 3 to 10 never played outdoors and that only 50 % of children practiced outdoor games at least 2 school days per week. A phenomenon of "disconnection" with serious consequences (obesity, attention deficit disorders, etc.).

In his book, Richard Louv chose to put a name to this phenomenon, since frequently taken up to describe a daily life in the process of accelerated artificialization: the “nature deficit disorder”. This "disorder" does not designate a medical diagnosis, but a set of symptoms, clinical signs and consequences of the tendency of our modern societies to increasingly isolate themselves in a sphere that removes, even "extinguishes", the experience of non-human world.

It is important to remember here that this estrangement affects all age groups.

In a study published in December 2022 , a team from the University of Leipzig materialized this distance by calculating the distance that separated individuals from natural elements: according to their assessments, this distance has increased by 7% over the past twenty years. Also according to their calculations, in the world, individuals would live on average about 10 km from a natural area.

To follow environmental issues as closely as possible, find our thematic newsletter “Ici la Terre” every Thursday. On the program, a mini-dossier, a selection of our most recent articles, excerpts from books and content from our international network. Subscribe today .

The sources of the nature deficit

Among the various causes put forward to account for this disconnection, let us dwell on the three main ones.

First, there is the phenomenon of soil artificialisation, a central element in the loss of biodiversity. This process has been growing in France 3.7 times faster than the population since 1981 , reducing people's experience of the natural world accordingly.

With 80% of the French population now living in “urban units” (more or less large), we are increasingly cutting ourselves off from the natural and possibly undomesticated world.

Then comes the culture of fears : we are "afraid" and even feel an aversion towards certain elements of nature.

Fear of the night, of wild animals, of insects, of touching the grass, of walking barefoot, of walking alone. Fear of the viscous, of the damp, of what is dead… But also hatred of the rain, the cold, the wind, of any natural element over which we have no control.

This repression links the experience of “nature” to the feeling of “danger” . Accompanied by a feeling of insecurity in urban areas, this fear contributes to overprotecting children and to forcing them to favor the “safe” interior to the “dangerous” exterior. A survey, made public in 2018 and conducted in more than ten countries in Europe and North America, referred to this as "indoor generations", literally spending their lives indoors.

Finally, we must mention the virtualization of the world: outside of work, we spend more than 4 hours a day in front of screens and the number of devices connected at home in OECD countries has quintupled between 2012 and 2022 (going from 10 to 50).

This virtualization would promote sedentarization and contribute to multiple disorders linked to our current lifestyles (cardiovascular diseases, obesity, type II diabetes, depression, anxiety and stress, mental fatigue, irritability and aggressiveness, etc.).

In full environmental amnesia

Another phenomenon which explains and amplifies the disconnection: what specialists in ecopsychology, this discipline which analyzes the relationship between psychology and ecology, have identified as "environmental generational amnesia" , leading each new generation to consider the environment in which she grows up.

There is thus a constant shift in the “reference” of the environment which results in the forgetting (due to a lack of experience) of its previous state. In his book on “new words for a new world” , the Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht speaks about this as “ecoagnosia”.

“With such a limited experience of nature to pass on to the next generation, each generation accepts an objectively impoverished nature as the norm […] nature eventually fades away and there is an extinction of experience. »

This philosophical, political and “economic” question arises moreover about the possible imaginaries of a world in which it would be a question of finding our place. After two centuries of profound transformation, where could the reference of a “natural” society be located?

This unprecedented situation in the long history of humanity calls us to deeply rethink our ways of life, but even more so our ways of doing things in the world.

Making a world means rebuilding a "diplomacy of interdependencies" between living beings, to use the terms of the philosopher Baptiste Morizot in his book Manières d'être vivant (2020). It is a matter of ensuring mutual understanding and an adjusted sharing of the environment, far from the pitfalls of human domination and the appropriation of the land. Making a world also means taking an integral part in the fabric of the living, which we will defend all the better as we know and love it.

“Reconnection” tools to explore

Throughout France, workshops and courses in practical ecopsychology or biophilia offer to revive these links to the living and to our feeling of interdependence.

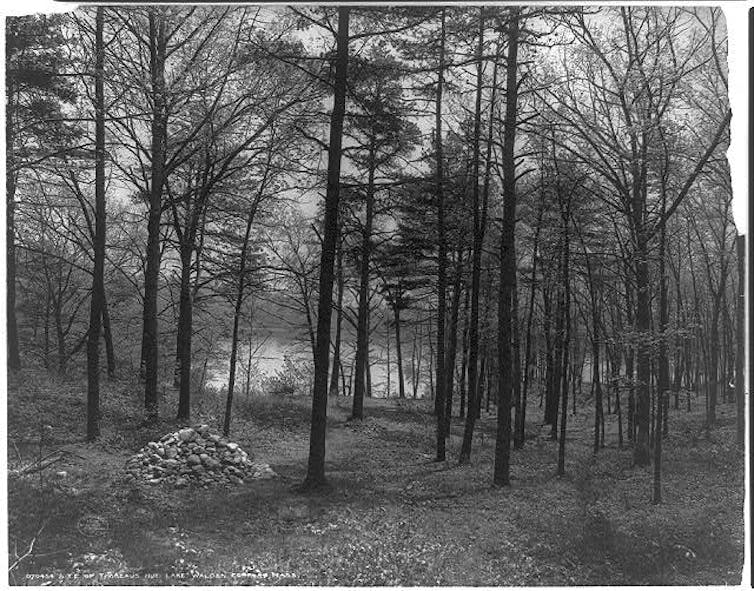

Many are also the guides to follow to open the reflection and imagine which paths this reconnection could take: let us quote again Baptiste Morizot, but also the photographer Vincent Munier or the anthropologist Nastassja Martin ; and, on the side of the “classics”, of course, the poet and naturalist Henry David Thoreau , whose work Walden or life in the woods (published in 1854) has become a bible for ecologists.

Some may also be curious to see how other cultures – one thinks for example of Asian, Amerindian or African spiritualities – develop adifferent, stimulating approach to relations with the non-human.

It is to be hoped that these changes will become accessible to all ages, in all environments (school, university, institutional, collective, private, prison) and all social classes, in particular by making natural cycles and processes more visible, by opening up the space of possibilities for imaginations and alternative lifestyles (such as school children, or ZADs for example).

And also by experimenting with alternative techniques of production, consumption, sharing of collective knowledge and know-how, of creating commons, like the low-tech philosophy that promotes simple and sober innovations .

Yoan Svejcar , independent researcher-practitioner in ecopsychology, is co-author of this article. ![]()

Romain Couillet , University professor, multi-disciplinary researcher, University of Grenoble Alpes (UGA)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .