Aerial view of a waterfall in Ecuador's Vilcabamba Valley, where a river won a historic court case in 2011. Curioso.Photography/Shutterstock

Diego Landivar , ESC Clermont Business SchoolOn March 30, 2011, something completely unprecedented happened in front of the Provincial Court of Justice in Loja, 430 km from Quito, the capital of Ecuador. The Vilcabamba River, plaintiff in a lawsuit , was able to have the courts recognize that its own rights were threatened by the road development project. The latter endangered the flow of the watercourse and was therefore stopped.

I had the chance to attend this trial and study what we call legal animism in two pioneering countries in the field: Ecuador and Bolivia.

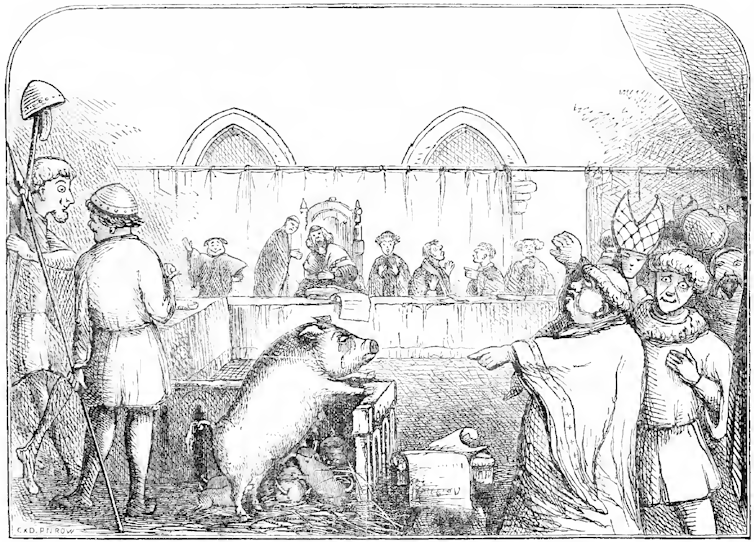

Today, from Uganda to New Zealand , various countries are following this path by opening their criminal systems to these legal approaches which allow a natural entity, an ecosystem, or nature as a whole to become a legal person , and, as such, to have rights. So many innovations which arouse the hope of certain environmental activists but also remind us how plastic and creative the law can be over the ages: since these trials in the Middle Ages where we could find animals at the defense bar , through India where a lawyer filed a complaint against a god to our contemporary times where no one finds it abnormal that a company can be considered a legal person.

The meeting of two world views

Delving into the genesis and evolution of the Ecuadorian and Bolivian experiences also allows us to see at work the different forms that legal animism can take, its possibilities and its limits. This is what I suggest you do.

Although South America may have been an innovative land in terms of legal animism, the expression was not born across the Atlantic. It appears for the first time from the pen of the French law researcher Marie-Angèle Hermitte . From the outset, the expression signals, in just two words, the meeting of two worlds, of two philosophical traditions with on one side an animist worldview, which Western thought has often constructed as its exact opposite and, on the other hand, the other, a system whose contours have structured European modernity.

In Ecuador, as in Bolivia, when we focus on the contexts of emergence of legal animism, we can find, in the background, the influences or frictions that emerge from the meeting of these two visions of the world, with both influences from North American environmental lawyers and a use of the divine figure of Mother Earth present in the cosmogony of the Andes.

The Constituent Assembly: moment of redefinition of life

Another point in common between these two countries is a very particular context: that of the constituent assembly. In 2006 for Bolivia, in 2007 for Ecuador, these countries experienced a unique moment that looked like a blank page: by having an assembly responsible for drafting a new constitution, it was the entire identity of their nation that is being redefined.

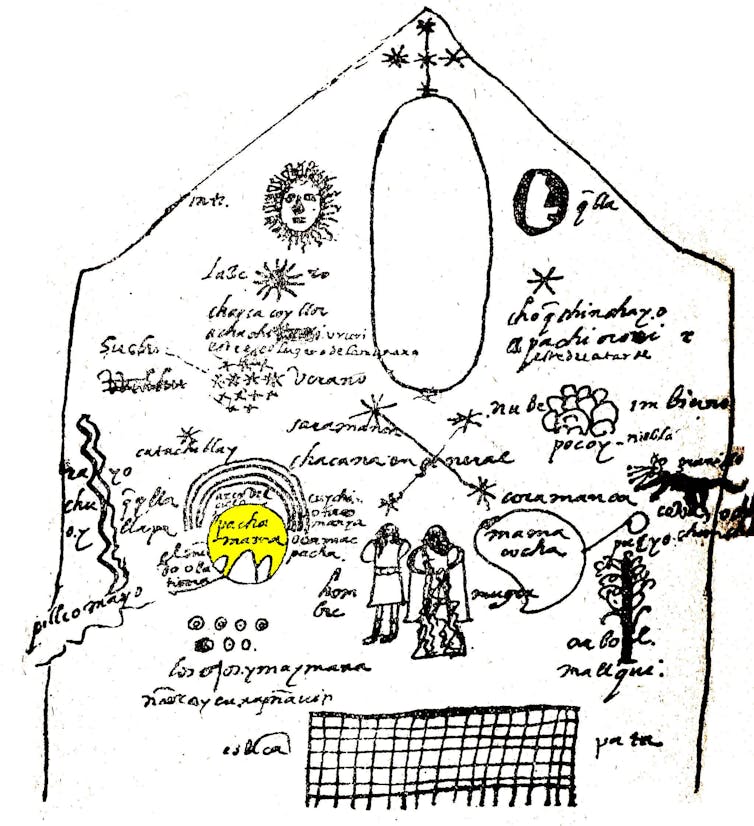

In both countries, these moments were supported, even awaited by the indigenous communities, and saw the emergence of the figure of Pacha Mama, an entity of Mother Earth in Andean myths whose name also evokes the meeting of two worlds since it is built around the term pacha , which means world in Quechua and Aymara, and mama , mother in Spanish. In this context, aspirations to provide nature with its own legal existence are rapidly emerging.

In Ecuador, legal animism is mainly supported within the Constituent Assembly by an intellectual elite close to new theories of law, influenced by the reflections of the American jurist Christopher Stone, who proposed in 1972 to endow trees with rights. To establish these ideas in the context of the Constituent Assembly, we then resort to a rereading of the indigenous knowledge of the country, where 80% of the inhabitants come from crossbreeding between Europeans and indigenous people, but where almost the entire population is claims to be Christian. Article 71 of the Constitution is thus born from these various influences and stipulates:

“Nature or Pacha Mama, where life reproduces and realizes, has the right to have its existence, the maintenance and regeneration of its vital cycles, its structure, its functions and its evolutionary processes fully respected. Any person, community, people or nationality may demand from the public authority the fulfillment of the rights of nature. »

The following article mentions the right to the restoration of an ecosystem, while 73 calls for the necessary precautionary principle for activities that could lead to the extinction of species, the destruction of ecosystems or the alteration permanent natural cycles.

The figure of Pachamama

In Bolivia, where the figure of the Pachamama is not just a simple folkloric entity from the past, we could see the constituents debate at length about its attributes, with on the one hand, inhabitants of the High Plateaux who honor this divinity at daily, and, on the other, actors from the Bas Plateaux and the South of the country having a rather vague notion of Pachamama.

The scope of action of Pachamama was also hotly debated: if Mother Earth is omnipresent, should we include all living things within her? What are his limits ? I was thus able to attend a debate which tried to find out if, by giving legal existence to Pachamama, it would now be possible to bring a lawsuit if a mosquito bit a human, and to see if this was desirable.

These reflections lead to a conceptualization of Pachamama as an open and collective entity, a Mother Earth crossing all planes of existence and therefore to be protected as such, in order to avoid endless reflections aimed at circumscribing what could or not be included in Pachamama. Perceived as the mother of all things, she is found in all entities in the world. In the new Constitution of January 22, 2010, ten articles in total mention Mother Earth in these terms:

“Mother Earth is a dynamic living system comprising an indivisible community of all life systems and living beings, interrelated, interdependent and complementary, which share a common destiny. Mother Earth is considered sacred according to indigenous peoples. » (article 3)

Articles 5 and 6 establish the legal framework for Mother Earth considered as a “collective subject of public interest” and ensure that as such, all Bolivians can exercise the rights of Mother Earth, while must, however, respect both individual and collective rights.

Article 7, finally, lists the seven rights of Mother Earth: right to life, to biological diversity, to water, to pure air, to balance, to restoration, right to not be polluted.

The article you are reading is offered to you in partnership with “Sur la Terre” , an AFP audio podcast. A creation to explore initiatives in favor of ecological transition, everywhere on the planet. Subscribe !

The incarnations and limits of these new rights of nature

This new relationship with the living thus established by the Constitutions, what were the consequences and concrete applications of these new legal tools? Once again, Bolivia and Ecuador took quite different paths.

The desire of Ecuadorian constituents to provide concrete legal tools quickly gave rise to legal actions, first and foremost this famous Vilcabamba River trial, in the Loja region. If this legal action had been initiated by environmental activists who were well versed in the new possibilities of the law in 2011, we have since seen more diverse actors in Ecuadorian society initiate procedures .

The tools proposed by the new Constitution have notably made it possible to overcome a limit very quickly reached by ecological battles throughout the world: that of the difficulty of isolating responsibility when it comes to the environment, attribute responsibility to a project, an organization, a person, sometimes located outside the borders of a country where the damage is suffered. It is in particular by mobilizing the notion of the precautionary principle and universal jurisdiction that Ecuadorian justice has been able to avoid remaining locked in these questions.

Thus in November 2010, Ecuadorian citizens, but also Indian, Colombian and Nigerian citizens filed a complaint before the Constitutional Court of Ecuador to demand that the company British Petroleum, responsible for a colossal oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, return public information related to the ecological disaster and its impact, and oblige it to take the necessary measures to repair the damage generated. The citizens in question were not direct victims of the oil spill and therefore did not file a complaint to protect their rights, but those of the ocean. If the complaint was investigated, however, the judges finally decided to kick in by putting forward another constitutional framework which imposed a notion and a perimeter of territorialities on cases.

In Bolivia, the work of the Constituent Assembly did not really go in the direction of establishing tools to easily take legal action to defend the rights of nature. However, the drafting of this new Constitution centered around the figure of Pachamama was not without effect.

Firstly, a certain disillusionment could be noted in the face of the gap between the ambitious ideals built around the rights of Mother Earth and a return to normal, with the continuation of projects for the exploitation of natural resources. The government thus found itself in a difficult position by proclaiming Mother Earth sacred on the one hand, and by inheriting, on the other hand, the day-to-day management of all extractivist economic sectors, even by developing them.

This divergence fueled a certain anger and the figure of Pachamama was thus one of the pivots of certain struggles such as, for example, that of the movement opposing the construction of a road leading to the region of Tipnis, a nature reserve of the Bolivian Amazon. Peasant, indigenous organizations and civic committees have, in this context, notably opposed the “developmental” arguments of the Bolivian government with the rights of Mother Earth, guaranteed by the Bolivian Constitution.

Having strong support from the population, particularly during two marches towards the capital, this movement first won a first victory , with the promulgation of a law establishing the intangibility of the national park and the abandonment of the highway project in October 2011, before finally backpedaling in 2017 . Over the course of this issue, President Evo Morales has in any case lost much of the support of the indigenous populations.

Backpedaling possible in all directions

What can we learn from these legal innovations? If they were able to allow legal and political actions, the law cannot do everything, and above all remains, depending on political situations, flexible in the direction of environmental fights as well as in that of extractivist injunctions.

Backtracking can be legion in one direction or the other. Recently Australian legal news was able to show this. In 2019, the indigenous Aṉangu people decided, despite the significant financial windfall that this represented, to ban visits to Mount Uluru , a sacred site whose mass tourism was aggravating the erosion and pollution of groundwater.

In recent years, Ecuador and Bolivia have remained faithful to their reputation as a laboratory of legal innovation, with, for example, discussions carried out on a possible opening of the right to objects within the Bolivian Mother Earth Authority then headed by Benecio Quispe.

Faced with the global problem of waste management, the Mother Earth Authority had begun discussions with indigenous community leaders and union leaders on the legal rights from which the objects and goods produced could benefit , such as the right to hope. of maximum life, a right to care, to repair, not to be abandoned... If this avenue had not ultimately been retained, it showed, once again, how legal tools can allow us to redefine our link to our ecosystems and modernity.

This article is part of a project bringing together The Conversation France and AFP audio. It benefited from financial support from the European Journalism Center, as part of the “Solutions Journalism Accelerator” program supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. AFP and The Conversation France maintained their editorial independence at each stage of the project. ![]()

Diego Landivar , Teacher Researcher in Economics, Director of Origens Media Lab, ESC Clermont Business School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .