The greatest revolutions take place in silence. Slowly, without our realizing it, they transform, one by one, all the elements of our daily life until the day when, looking up at our existence, we realize that we no longer recognize it. The Internet came into my life in 1999. My parents had just invested in a computer, and there, on this digital screen, an innovation born of the mind and the hand of man, a new world of possibilities could be guessed. . At the time, I admit that I didn't understand much, my perplexity being matched only by my lack of interest. I hadn't realized that the world as I knew it had just changed forever, nor that my relationship with nature was going to take on a new dimension.

While more than half of the world's population now lives in cities , in environments where digital technology predominates, the relationship of humans to nature in post-industrial societies is at best complicated, at worst non-existent. We often see nature through the prism of our culture . We don't like it that way anymore. She seems less threatening. In the era of the digital revolution, where we spend more and more hours in front of our phone, computer or tablet screens, reconnecting with nature seems to be a solution to modern chaos.

Nature as a remedy: yesterday and today

The notion of nature as a remedy for the ills of civilization is not new. Examples of returning to nature in response to an urban and/or industrialized context abound, from antiquity to current experiences of urban farms and ecovillages , through the transcendentalist movement and the counter-cultural period.

In the 19th century, Henry David Thoreau explained, in Walden or Life in the Woods , his decision to live in a cabin in the forest, away from society:

"I was going into the woods because I wanted to live without haste, to face only the essential facts of life, and see if I could learn what she had to teach me, and not have to discover , at the time of my death, that I had not lived. »

In the 20th century, Helen and Scott Nearing , emblematic figures of the "back to the land " movement that affected the United States in the 1960s, decided to leave stable jobs in New York to live off self-sufficient way on a farm in Vermont. Today, in the 21st century, it is through science that we are redefining our relationship with nature. More and more researchers are demonstrating that human health is intrinsically linked to nature, and even that the benefits experienced are proportional to the time spent outdoors. They confirm today what man has always felt instinctively: spending time in nature is vital to us.

I grew up in the city, or rather between city and nature, since every city always has a bit of nature, through the trees that line its avenues, the parks scattered here and there. When the Internet arrived, slowly but surely, my daily hours became hours spent working in front of a screen. The need for nature has become more intense, the green parenthesis after hours on the computer more life-saving, a breath of vital but limited oxygen.

While the use of digital technologies promotes anxiety, depression and attention disorders , numerous scientific studies prove that, on the contrary, spending time in nature restores our cognitive abilities and reduces our stress. David Strayer, a researcher at the University of Utah, explains that the prefrontal cortex, the command center of the brain, over-stressed by the use of the Internet and social networks, is in a state of almost permanent alert. However, it quits when the human being is in a natural environment, causing a decrease in Theta brain waves, and promoting creativity, emotional connection and even intuition.

Our ideas about nature: the human/nature dualism

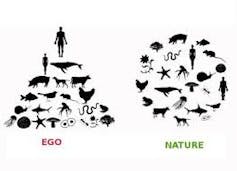

The effects of nature on the human brain may be clear, but our ideas and beliefs about it continue to evolve. As part of my joint supervision with an Australian university, I have to study the way in which aboriginal populations perceive nature. Their culture does not draw a clear line of demarcation between the notions of natural environment and hearth (house). The human/nature dualism, also called nature/culture dualism, which results in the separation we almost constantly, and often unconsciously, create between self and nature is a product of the Western belief system. For when we think of what nature is, what nature are we talking about? Of an idealized nature on which we affix the filter of romantic beliefs? Or of a nature perceived by the senses without the judgment of the intellect?

William Cronon, in his essay "Going Back to the Wrong Nature" , denounces the erroneous perception that Western society has of nature. Erected as an antithesis of civilization, nature becomes a wild and pure space towards which man, fleeing society, turns to recharge his batteries, find rest and reconnect with himself. It is a nature that begins where the city ends, a nature that is foreign to us and within which we are only passing through, a nature that we must leave to return home. This conception of nature exacerbates the separation between man and his environment. As Cronon explains:

“If we allow ourselves to believe that nature, in order to be true, must also be wild, then our very presence within it represents its downfall. Where we are is where nature is not. »

Do you really think as a human being that you are part of nature? Many people would answer yes. Now, do you think that the city you live in is part of nature, that there is no difference between this city and nature? Perhaps more difficult to design. You may be aware that the city you live in was built on a natural environment, which endures under the asphalt of roads and streets, that everything that makes up this city, including your home, comes from materials and components natural, that, just as concrete is only an assembly of materials of mineral origin (sand, lime, clay, etc.), plastic is made from raw materials such as oil, natural gas and the coal ?

And yet, it is difficult for us to accept that the city and nature can be one, that the city can be an extension of nature, just as nature is part of the city. It is difficult for us to accept that our home is above all this natural environment within which our houses are built.

Nature deficiency disorder: a modern disease?

Australian professor Glenn Albrecht denounces the chronic distress that human beings experience in the face of the transformations that natural landscapes have undergone since the industrial revolution. He coined the term Solastalgia to describe that feeling that something is wrong, that feeling of not being in our place, or, as he puts it himself, that feeling of being homesick even when we we are at home. From the Latin solacium (relief, appeasement) and algia (pain, suffering), this neologism evokes our visceral need for tranquility (which does not seem to find an excipient in an urbanized environment), as well as the link that we have lost with nature. .

The American journalist Richard Louv speaks of “ nature-deficit disorder” and denounces the growing tendency of younger generations to spend more time locked up in front of screens than outside discovering their natural environment. While the use of anxiolytics, sleeping pills and antidepressants continues to increase to cope with daily anxiety and stress, it may well be that the modern disease is a lack of nature.

While my thesis research pushes me to question fundamental beliefs about nature and our identity in relation to it, the progress of my work does not yet allow me to provide clear answers on this subject. However, taking time to go for a walk in the forest, swim in the sea, or simply read a book in a park are all ways to reconnect with nature. Japanese researchers have shown that walking regularly in the forest, (what they call taking a forest bath or Shinrin-yoku ), leads to a decrease in the level of cortisol in the blood, a drop in blood pressure and activates the system parasympathetic nerve, inducing a relaxation response. Today's world makes the use of digital technologies and the Internet inevitable, and since there is no going back, it is essential to find a balance in the use we make of them. Rediscovering and nurturing our connection to nature seems like a good starting point. ![]()

Mélusine Martin , PhD Candidate - History and Dynamics of Anglophone Spaces, HDEA (Paris IV) and Environmental Sociology (James Cook University), Sorbonne University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .